Regional Spotlight: Far West

Food System, Interrupted

By Amanda Faison

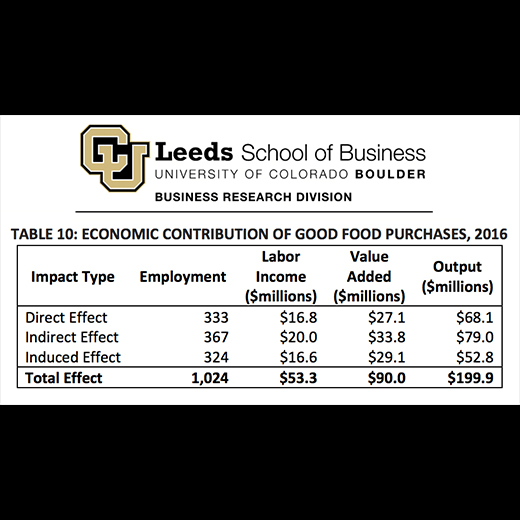

A disconnect exists in our food system, and much of it comes from underestimating the cost of good food. In California, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada—an area the Bureau of Economics defines as the Far West—it is often perceived that food is plentiful. In fact, in 2017 according to the 2018 Good Food 100 Restaurants Economic Report, the Far West contributed $56.9 million to the domestic good food system. But even in an area with bountiful growing seasons, a diversity of landscapes, and easy access to the coasts, sourcing carefully fostered produce, livestock, and aquaculture isn’t easy. Dig into each purchasing decision (in 2018 participating Far West restaurants scored in the 95th percentile for total good food purchases) and you’ll find a web of intricacies that range from unpredictable weather to labor woes.

To be a farmer anywhere in the world is to be flexible and solvent no matter what Mother Nature has in store. But in states like California and parts of Nevada this means facing severe drought and intense fire danger cycled through with deluge rains that flood fields and stunt growing seasons. “It’s nature, it’s agriculture, and we’re at the mercy of it,” says Stuart Berman, a high-end produce distributor based in Los Angeles. That precariousness, coupled with the toll of unending hard work, fluctuating crop prices, the high cost of labor, tiny margins, and insatiable demand for land is driving many away from the farm. “You know the Disneyland story, right?” Berman says. “An old Japanese family had a strawberry farm across from the original Disneyland. Disney wanted the land to build a parking lot or something and the father always insisted ‘I’m a strawberry farmer’ but when he passed away those kids must have been at the funeral with a pen in hand,” Berman says.

Julia Niiro, founder of MilkRun, a digital marketplace enabling consumers to buy directly from producers in and around Portland, Oregon, echoes a similar concern. “The farmer can’t continue to do it all—be the producer, the driver, the marketer, the retailer,” she says. And that’s where MilkRun comes in. Eighteen months ago Niiro took her background in farming and business-to-business advertising and launched a platform that not only connects farmers directly with consumers but also acts as the distributor. Think of it as a farmers’ market crossed with Instacart: You place an order, the farmer/rancher/baker prepares the food and MilkRun delivers it to a cooler on your doorstep. Thus far, 65 ranchers and farmers have signed up and 5,000 subscribers place an average of 400 orders a month. Niiro realizes that this is a small, local solution in a monster-sized supply chain, but she thinks that the model can work elsewhere. In fact, she’s emphatic that to save small farms it has to. “It’s [the public’s] responsibility to build the systems that can help producers scale in a responsible way so we don’t have to rely on the standard supply chain that’s based on the global market,” she says.

Responsibility weighs heavily on George Frangos, co-founder of FarmBurger (five links), a fast-casual burger concept with locations in California and the southeast. Frangos, along with co-founder Jason Mann, who is an organic farmer and rancher, have crafted a restaurant entity with a goal of connecting soil, animal, plant, rancher, butcher, chef and customer. This is a restaurant concept with a clear conscience. But when asked about issues facing the Far West region Frangos says, “I think labor is a key piece everywhere. It really affects all segments of the food chain from farmers to distributors to restaurant staffing.” Frangos’ background running high-end restaurants coupled with Mann’s experience farming and ranching, affords them a birds-eye view into the industry as a whole. “I'm a huge fan of higher minimum wage and a lot that California has been a vanguard of but you have to couple that with affordable housing, transportation policy, you have to address both sides,” Mann says.

The food chain is by nature intricate, complicated, intertwined, and sometimes uncontrollable. That complexity is magnified when you look at the good food system because it’s smaller and more delicate. But this sector also thrives on innovation, resilience, and transparency, which results in a better understanding of how food ends up on a plate. An even more dedicated public will create a demand for better systems, better wages, and a better ways of life across the Far West and beyond.

Photo above: Brandon Stein, Scarborough Farms (Tender Greens original farm partner), Oxnard, California

The Good Food 100 2017

© 2021 - Good Food Media Network