Regional Spotlight: Southeast

The many issues facing the Southeast’s Good Food system are as diverse as the region itself.

By Amanda Faison

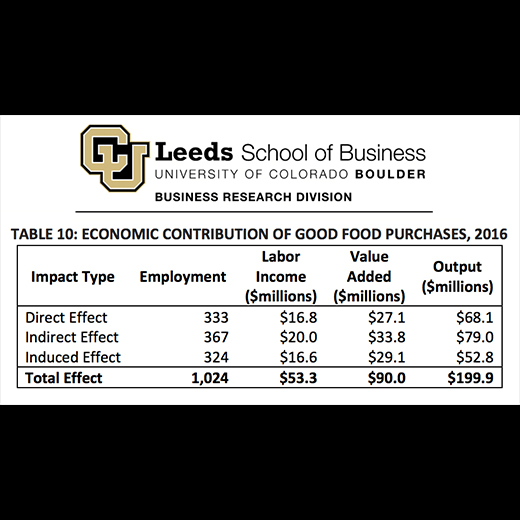

To say the Southeast is a large and diverse region is an understatement. According to the Bureau of Economics, the area is made up of Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida. A solid 15 percent of the Good Food 100’s participants (or 19 restaurants) reside in this part of the country. In a region so expansive, it should come as no surprise that the issues facing the good food system (which had a total economic impact of $14.9 million in 2018) are equally wide-ranging.

For Stephen Phelps at Indigenous Restaurant (six links) in Sarasota, Florida, the number one challenge this year has been battling the effects of Red Tide in the Gulf of Mexico. The toxic algae bloom put a strain the local fishing, restaurant, and tourist industries. “It was on and off for five months…some of the big hotels were at 30 percent occupancy,” Phelps says. “It was so bad that a good fishing captain I know had to pick up a job in a restaurant.” For Phelps, whose restaurant is centered on sustainable and local seafood, it meant menu juggling and additional staff training. Indigenous has long been known as “an educational restaurant,” says Phelps. Meaning that the staff hands out Seafood Watch pocket guides and prides itself on guiding guests on smart seafood choices. This year, that established trust paid off in spades. “[Customers] still came here. I was lucky enough to have my status to assure people that I’m not feeding them fish that has poison in it,” Phelps says.

For Mike Lata, chef-owner of FIG (six links) and The Ordinary (six links) in Charleston, South Carolina, also sites seafood as an area of concern. “The half-empty perspective is that our fleets are diminishing and our regulations are tightening so fishing (which is our resource, what Charleston has, our precious competitive edge and our inspiration) is struggling,” says says Lata, whose restaurant FIG is nominated for a 2019 James Beard Award for Outstanding Restaurant. But Lata is also quick to point out what’s going right: the local oyster industry. “It’s the best story in all of food. What was once depleted is now being restored and our waterfront is active again as part of the food source,” he says. “Ecologically [oysters have had] a positive impact. We’ve got beautiful, really interesting waters now.” And yet, this burgeoning industry (last year The Ordinary grossed a half-million on local oyster sales), also brings complaints from homeowners who are pushing back because they don’t like the look of the floating oyster cages. It’s a classic tale of one step forward, two steps back.

Camila Ramos, co-owner of All Day (five links), in Miami knows that feeling well. Her struggles come from the isolation of Miami’s extreme southern location. “When people talk about the Southeast, they’re talking about the South and the East but not south Florida,” she says. And its not just food movements (like specialty coffee or natural wines) that take forever to find their way to this city of nearly 500,000, it’s the understanding of what it takes to source and serve local produce in a place with too much sunshine. “Our biggest issue in South Florida, zone 10b, is that we only get local produce production from November to May. In the summer we have very little in season that isn’t tropical fruit,” Ramos says. Because of that there’s little awareness as to what’s truly local and what that truly costs. Thirteen dollars for a salad with local greens will make most Miamians balk, which creates a tough market for small restaurants wanting to support area farmers.

In Roanoke, Virginia, chef Matthew Lintz of Local Roots, (six links) has the opposite problem. “Finding product isn’t difficult,” he says. “I have to turn down farmers.” The challenge comes with sourcing ingredients that are unique and interesting. Lintz has begun working with younger, more progressive farmers to grow items such as sunshokes, celery root, salsify, burdock root, cardoons, and different varieties of squash—many of which are indigenous to the area. Once he has product in hand, he turns his attention to educating the Roanoke diner. “I try to strike the balance of something familiar and something that’s prepared in a familiar way but new ingredient,” he says.

In Asheville, North Carolina, the food scene is thriving, says chef-owner Katie Button of Cúrate (six links). “The support for local farmers and producers—it’s the driving force,” she says. “It’s what allows more interesting, independent producer-concepts to be created. And the more we support those producers, the more things pop up.” That degree of depth also presents its own challenges: Purchasing from a multitude of local farmers requires a lot of oversight (from both sides), which can be overwhelming for a chef de cuisine. To address that issue, Button, who is a 2019 James Beard nominee for Best Chef Southeast, created a purchasing manager position. “One of the best things we’ve done was put one manager in charge of purchasing for the restaurants,” she explains. “She has time to make connections, she keeps an inventory with an eye on food cost, and she’s increased local farm purchases 30 percent in one year.”

There is no one voice that can speak for the challenges or solutions for a region as diverse as the Southeast. But when forward-thinking chefs and restaurateurs band together, stick to their principles, and think creatively, more good happens than ever before.

The Good Food 100 2017

© 2021 - Good Food Media Network