Story of Origin

Founders Sara Brito and Jeff Hermanson dish on how the Good Food 100 Restaurants came to be.

By Amanda Faison

The Good Food 100 Restaurants, which launched in February 2017, is a national survey and list of U.S. restaurants and food service companies designed to educate eaters and celebrate restaurants for being transparent with their purchasing practices.

Q: Can you tell me about the genesis of the Good Food 100 Restaurants? How did it come to fruition?

Jeff Hermanson: I’ve been in the restaurant business for more than 40 years, and I’ve always been impressed with how the restaurant industry and chefs, in particular, have driven social change and made contributions to better our lives. Recycling was largely pioneered by the restaurant community and chefs have gravitated to nonprofits dealing with hunger. Fast forward: I lived in Crested Butte and got involved in producing the food and wine event about a decade ago. It was fun bringing celebrity chefs through the Front Range to Crested Butte but after several years the chefs, and in particular Kelly [Whitaker of Basta in Boulder] and Alex [Seidel of Fruition and Mercantile Dining & Provision in Denver] wanted to do something different. They were tiring of doing an indulgence-related event and they recommended that I meet with Sara. The timing was fortuitous because Sara was leaving Chefs Collaborative and I asked her if she would get involved with Crested Butte Food and Wine. A few months later she drove an agenda called Eat. Drink. Think. The format had been fairly generic food and wine festival, but our goal was to do something that was different. It was the beginning of encouraging people to think about food-related issues.

Sara Brito: Eat. Drink. Think. was definitely the beginning. I remember Jeff asking, ‘Where is this going?’ That’s him, always looking ahead. I was focused on the task at hand and fully immersed—I have to be otherwise I might miss the opportunities for insight. In August, I went to him and said I think I have a big idea. I put the pieces together and how Eat. Drink. Think. could connect with this economic impact studyand network that we came to call the Good Food Media Network.

Q: How does the Good Food 100 differ from Chefs Collaborative?

SB: The Good Food Media Network's mission is broader, and there is no cost to participate. Historically, chefs Collaborative has been primarily industry-focused. It’s a wonderful member-driven organization that serves its members through education. We believed there was an opportunity to be industry and eater-focused by leveraging data from the industry and chefs to provide value to eaters. If you don’t create something that matters to both the industry and eaters, you’re going to lose the attention of chefs. By serving the needs of restaurant guests, we are ultimately serving the needs of chefs and restaurants. Eaters want to know where their food comes from. I like the example of the grocery industry: We know people are looking at labels with wonder and worry. We as humans are not segmented people, we don’t act one way in the grocery store and go to a restaurant and act differently. The fact that eaters are wondering where their food is coming from is going to impact the restaurant industry.

Q: Can you elaborate on why you prefer the term “eater” to “diner”?

SB: I like to say eater because I feel like it’s a unifier. We are all eaters. It gets at this basic human need to eat, regardless of where you choose to eat. Maybe it’s at a restaurant, maybe it’s at a corporate cafeteria, maybe it’s in a public school lunchroom, or maybe it’s at home. What I like about “eater” is there’s less risk of being associated with the one percent of the population that eats at fine-dining restaurants. We hope the Good Food 100 will serve the 99 percent and the one percent.

Q: The Good Food 100 champions food transparency but what else is rolled up in the Good Food Media Network nonprofit’s mission?

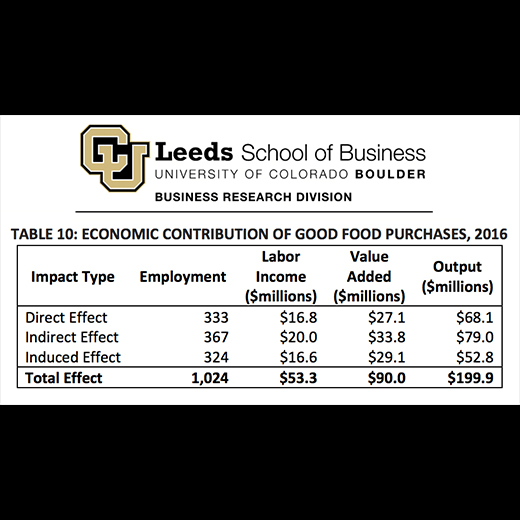

SB: The GF100 puts transparency into dollar-and- sense speak because it’s based on actual purchases. Restaurants and food businesses are economic drivers in the local community and the mere decision of choosing to buy from one place versus another could add jobs. With my basic understanding the chain goes like this: When chefs put money into a regional producer, that producer then spends money via equipment and staffing, and those additional expenditures put more money into the economy. When you think of food this way, you start to have a different conversation about good food.

JH: Anecdotally Chipotle has some good examples. I think Chipotle would acknowledge that 95 percent of sales are driven by the price and five percent by the mission but Chipotle single-handedly drove the idea of hormone-free pork. The company has dramatically affected change for the better in our food supply just by writing their vision and their goal.

SB: I think that’s a great example. Many restaurants and consumers would not be able to buy Niman Ranch hormone-free pork if Chipotle hadn’t created the economy of scale. That’s the kind of change I want to see. I think it happens in conjunction with not just the fine-dining restaurants, but by also having fast-casual players, food service, and distributors on board.

Q: Unlike a health inspection, the Good Food 100 isn’t meant to shame businesses, rather its mission is to drive the industry forward.

SB: I truly believe that everyone who takes the survey deserves to be recognized. What we’re really doing this year is a national pilot. We’ve said from the beginning that the survey isn’t perfect, the economic assessment isn’t perfect but we’re committed to this journey of adding our bit to changing the world. It’s so inspiring to hear from the restaurants. We had this hunch that transparency was important but it’s clear these restaurants need this because they need to tell the story of why good food is better for their guests to make their business models work. I got great insight from one of the people behind the Fortune 100 Best Places to Work list: In the early years, the list will matter most to the people who are on it. It’s going to take time to make the list mean something to eaters and make it a compelling way for eaters to make decisions about how they eat and spend their money.

Q: It’s early on but are you hearing that taking the survey is changing the way restaurants and food businesses operate?

SB: We’ve only been around (officially) for eight weeks [at the time of this interview] but already requests from chefs and restaurants participating [in the Good Food 100 survey] have provoked Growers Organic, a local distributor, to change the way it reports data to better serve its clients. When chefs take the survey, we suggest reaching out to their distributors to more easily track purchases. Even better, when distributors start asking the questions, they can better know where their food comes from. When restaurants know this information they can be more transparent and pass that along to their eaters. It’s not realistic to think of restaurants as buying only from individual farms. We need to get distributors on board and stop looking at them as the enemy.

Q: How will Good Food 100 affect other industries?

SB: We’ve already gotten requests from others in the industry like purveyors and distributors who have asked if I could create a survey like this for them. They feel like they’re making significant investments in being purveyors and distributors of good food and they want credit for those decisions. We had a producer who took the survey and it shows me that restaurants are not the only ones interested in transparency. It’s impacting every facet of society from grocery, to purveyor, distributor, to restaurant, to eater. It’s too early to say if we would pilot something for those sectors but we’re open.

Q: Why did you decide to establish the Good Food Media Network as a nonprofit organization?

SB: We could have created this survey and turned ourselves into the next Zagat that gets sold to Google, but we wanted it to be educational in focus with a mission driven to serve the industry and eaters.

Q: Why is now the time for something like the Good Food 100?

SB: When we piloted the economic impact study in 2015 and discovered that 3.6 million dollars in purchases had a 7.4 million impact that surprised even the chefs. In general, chefs are working in isolation just trying to keep their doors open. They had no idea that their food purchasing decisions had such an impact. This is our first attempt to measure and build the case that good food matters beyond the dinner table. I’ve been in the food world for almost 20 years. I’m tired of talking, I want to get things done and move things forward and show how we’re making progress. Let’s do this.