Regional Spotlight: Great Lakes

By Amanda Faison

The biggest issue facing the food system in the Great Lakes region (an area defined as Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio according to the Bureau of Economics) is perception, says Jennifer Rubenstein, the publisher of Edible Indy who has also done marketing for restaurants like Spoke & Steele (5 Links) in Indianapolis. There are two parts to this: “One, I think people don’t recognize that we have a flourishing food system here—we’re not just corn, soybeans, pigs, and dairy,” says Rubenstein. And two, “There are a lot of people who are hesitant to believe what’s written on a menu because a lot of terms used—farm to table, local, organic—despite being true, have turned into a marketing nightmare,” she continues.

It’s true that reading a menu can be a minefield (read Laura Reiley’s “Farm to Fable” story for proof) but that’s often where mission-driven restaurants dedicated to telling a farmer or producer’s story really make an impact. “Smaller restaurants are trying to capture an audience that wants a sense of local,” Rubenstein says. (Also, cue the Good Food 100, which helps diners navigate their way to restaurants and chefs making a difference.)

Frank Turchan, the executive chef of the University of Michigan (2 Links) in Ann Arbor, is quick to point out that you don’t have to be small to make a difference. He is responsible for feeding an average of 27,000 students a day and he takes great pride in serving as much Michigan-grown and raised product as possible. And the numbers are big, like 70,000-80,000 pounds of Michigan-grown potatoes annually—a number that has increased significantly in the last year. “A year ago I invited to speak to the potato board,” Turchan says. And since then he’s increased his orders for local potatoes. “Seventy percent are purchased from Michigan, except for the potatoes we use for french fries and that’s only because that variety doesn’t grow in Michigan,” he says. In addition, the university has built up herds of local cattle and about 70 percent of the pork served in the dining halls is raised 250 miles from Ann Arbor. Chicken comes from Ohio less than 100 miles away. Students’ consumption of beef has dropped recently because “we’ve increased our blended burger [patties made with a combination of beef and mushrooms], which, although good for the environment and student health, is taking away from the local spend,” Turchan explains.

And that’s just the beginning. Turchan who graduated from the Culinary Institute of America says, “We’re trying to do a lot more. They call me the Modern Day Forager because I’m always looking for small farms.” One such success is a deal struck with a fisherman father-daughter team who harvest white fish. For three years, Turchan has been buying 15,000 pounds of fish directly from them. That’s a win for both the university and the fishermen. (Given the proximity to the Great Lakes perhaps it’s not surprising that the nine participating Good Food 100 restaurants in the region, score highest in the fish and seafood category at 94 percent.)

The one area Turchan says he’s struggling with is labor of all levels, from the professional level to basic cooks, dishwashers, and kitchen cleaners. Turchan partially attributes this to a change in focus for students. “We used to employ 1,500 students. This past year we only had 400,” he says. “The biggest reason is peer-to-peer, they don’t want to serve each other.”

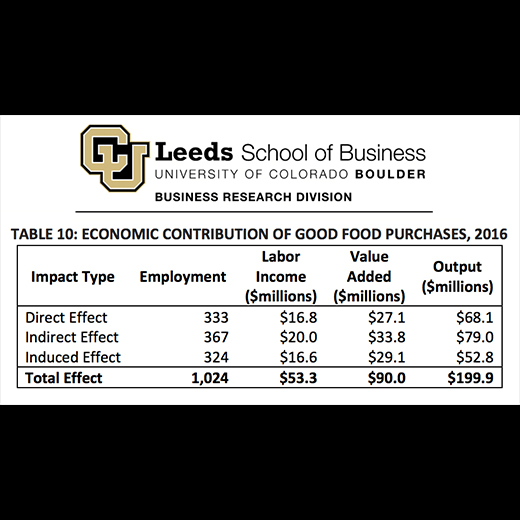

On the flip side, Rubenstein sees tremendous promise in the younger generation’s devotion to a good food system. “A lot of college students and new graduates actually budget for the local movement,” she says. “[They are] going to push in the direction of a sustainable food system,” she says. “That is where the system is going right.” And when the good food system has a $255 million dollar impact nationally, that’s a big deal not just for the future but for the economy as a whole.

The Good Food 100 2017

© 2021 - Good Food Media Network